Teaching and learning are arguably two of the most intriguing human activities. In this article, Nick Alchin brilliantly wades through the subtle layers of simplicity and complexity that manifest in the classrooms.

(Image by Ralf Kunze from Pixabay)

I am a great believer in seeking simplicity, and it troubles me that it often eludes me in my professional life. As far as I can see, while principles may be simple, operationalising them is complex.

I was, for example, recently explaining our approach regarding awarding grades on report cards to parents. A somewhat exasperated father asked me why can’t you just make it simple? I had some sympathy – if you’re not an educator, it probably seems like assessment should be easy and two approaches immediately spring to mind. Set a test, and award the top 10% (say) the top grade, the next 20% the second top grade (say) and so on. Or, award everyone who gets over 90% (say) the top grade, between 75% and 90% (say) the second top grade, and so on. Simple.

The trouble is that the simplicity here is achieved at the expense of meaning (the first, surprisingly common, method above actually awards a grade to a student on the basis of the performance of other students!). If our purpose in assessment is to measure what a student understands, and not simply to rank students in some order, then as any parent or teacher will know, any measure is just a measure, not a true representation. That measure will vary from day to day, depending on how a question it is asked and interpreted, what mood the child is in, what happened with his or her friends earlier that week and so on. And then there’s the question of how you would assess several hundred (or more) students’ understandings in robust and reliable ways if you were accountable for getting it right under high stakes circumstances. And then there’s the fact that by awarding one grade, you may prevent a student from believing he or she has the capacity to achieve a higher one. And then there’s the fact that different cohorts and classes have very different characters. It’s not simple.

My point here is not to get into assessment issues (I have written here and here on grading); it’s more to think about the fact that simple solutions are easy to think of – and almost certainly wrong. If these matters were simple, we would have solved them decades ago and not be talking about them now. That’s the message I drew from a letter from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation a few years back. I have full admiration for the Foundation; they are doing spectacular work in many areas and are also seeking to impact education, so I was interested to read the letter from Sue Desmond-Hellman, Gates Foundation CEO. After a decade of deploying huge resources, they are moving away from simple large-scale solutions to more incremental ways which draw on local tailored systems, and which recognise complexity.

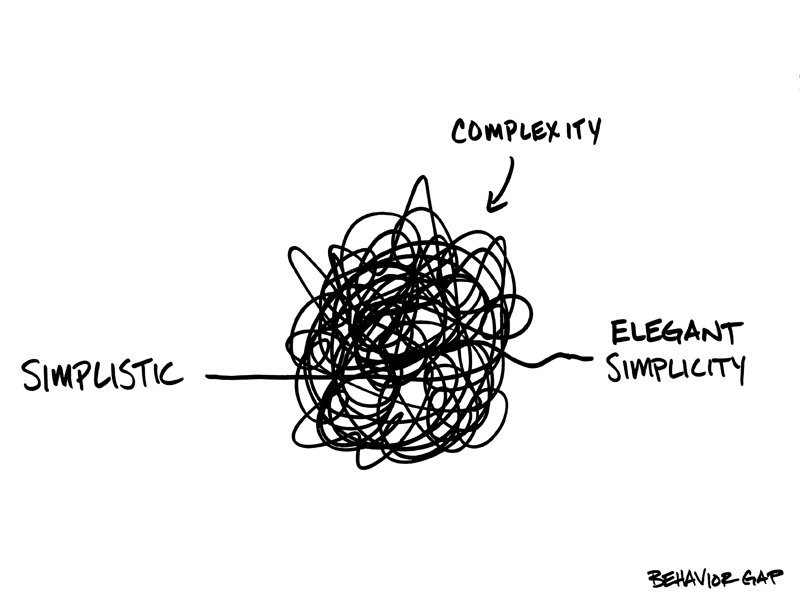

complexity to avoid being simplistic.

That’s a new and very welcome move and a different approach to earlier thinking. In the early 2000s Gates was convinced that the real problem with many schools was that they were too big, and that schools no bigger than 500 would do a better job. So build smaller schools – simple! Alas, many hundred of millions of dollars later, it proved to be a bit more complicated than that and that initiative has been dropped. The next idea was that teachers should be financially incentivised to get better performance. So re-design the evaluation system – simple! But the experiment started in 2009 in Florida program, evaluation system and all, was dumped at great expense having made no real difference to students.

Over the last 17 years, the Foundation has spent some USD3 billion for what seems to be fairly meagre results; and has now moved on to curriculum development and digital resource creation – now recognising, in their own words that no one knows teaching better than teachers. That approach is not simple – there are many disciplines and platforms and teaching remains as much art as science. This slowly-slowly approach does not promise radical breakthroughs – but that’s simply a recognition of how the world is rather than how we might like it to be. This reflects not a lack of ambition or drive, but a pragmatic (I am tempted to say business-like but that’s another story) recognition that it’s not simple. We’re facing the fact that it is a real struggle says Desmond-Hellman. And when she says it is really tough she means it’s hard to know what to do because the task is complex.

So, to return to the question ‘why can’t you just make it simple?’ I guess the answer is simply that we do not know how to do so. Perhaps we will one day, but we are not there yet.

Note: This article was originally published in June 2016 in Nick’s personal blog ‘Education, Schools and Culture’. Please visit his blog for more such profound thoughts and deep insights into many things related to Education.

Nick has taught in holistic, values-driven schools schools since 1995, first teaching Theory of Knowledge and Mathematics at UWCSEA Dover and subsequently at the International School of Geneva in Switzerland. After working as Director of IB at Sevenoaks School, UK, and as Dean of Studies at the Aga Khan Academy in Mombasa, Kenya, Nick returned to Singapore to lead a team establishing the UWCSEA East High School in 2012 as the High School Principal. He was appointed Deputy Head of East Campus in 2016 and took up the position of Head of East Campus in January 2021.

IB Chief Assessor for Theory of Knowledge from 2005 to 2010 and Vice Chair of the IB Examining Board from 2007 to 2013, he is a textbook author, IB examiner, workshop leader and consultant who writes and speaks widely on various educational matters.

Nick has a bachelor’s degree in Natural Sciences from Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, postgraduate certificates in Engineering and Education from Wolfson College, Cambridge and Manchester College, Oxford and a Master’s in Educational Leadership from the Open University.

An avid reader, Nick also enjoys running in the heat, evening walks in the cool and baking bread each weekend. His three children enjoy activities from volleyball to podcasting to drumming, and Ellie, his wife, is Director of Teaching and Learning on Dover Campus. As a family they enjoy travelling across the region (when they can!), sampling new food, and enjoying the great outdoors.

2 comments