The art of teaching is often about finding the sweet spot between knowledge and understanding where learning will happen. This spot is different for every student on every task on any given day. Curriculum materials can’t provide this kind of specificity but they can provide this kind of flexibility.

Understanding is to education what entropy is to physics, emergence is to complexity and the sublime is to aesthetics. Stretching the analogy further (perhaps too far), it might be what heaven is to religion. What each of these concepts has in common is both a level of significance that makes them central to their disciplines but also a level of abstraction that makes them very difficult to define. We can feel that concepts such as beauty, order, emergence and understanding make sense, but it is very difficult to describe exactly what they are.

In education, knowledge is much easier than understanding to define and recognise. A knowledge question such as “what year did Shakespeare die?” is unambiguous and easily taught and learned – for this reason it is often prioritised in high-stakes assessment. Understanding is hard. An understanding question such as “why is Shakespeare so important to our culture?” is much more of a challenge to teach and to assess. Indeed, “knowing” whether a student has “understanding” of the concept remains endlessly problematic; understanding whether a student has understanding is interestingly less so.

While wrestling with what it means to teach for understanding, I’ve been thinking about lego. I have a lego analogy I’d like to try out: as you read this, I hope you’ll join me to take my analogy for a spin and think critically about how it performs.

Teaching for understanding might be a bit like learning with lego blocks. Imagine I want to teach Amrita and Bill an understanding of what a house is. I’m going to give each a pile of lego blocks to make a house, but I’m going to teach each one of them quite differently as I work to build understanding.

I give Amrita her pile and say, “Amrita, here’s a big pile of lego blocks. What I want you to do is make a lego house. You can use any of the blocks you like but do your best to make a great house.”

I give Bill his pile and say, “Bill, here’s a big pile of lego blocks and here’s some great instructions written by the lego people in Denmark to help you make a house. Follow those instructions and I’m looking forward to seeing your house.”

Amrita and Bill each start working away and eventually finish their houses. Amrita makes her house very quickly but then changes her mind and starts again. In fact she changes her mind quite a few times as she works, adjusting and adapting as she goes. Her final house takes her a while to build and it’s a bit wobbly in places but a good achievement nonetheless.

Bill, a methodical worker, follows the instructions carefully and builds a lovely house. He finishes his house quite a while before Amrita finally gets hers done and he’s able to sit back and admire his carefully crafted handiwork.

Who has learned what? Who has gained knowledge and who has understanding? Here’s some thoughts.

Through experimentation, Amrita has learned about what does and doesn’t work when you are putting things together. She has had to reflect more critically on what the concept of a “house” might be as she envisioned the final house she was creating. Her learning was mostly limited to what she already understood about the concept of a house but she has a richer understanding of how to organise the blocks and herself to create a final vision.

Bill has had a very different experience to Amrita. By following instructions, he has implicitly learned one way that a house can be structured. He may not have understood in the same detail as Amrita why his house is built the way it is (what, for example, might go wrong if he were to alter some of the structure), but he may also have a complex vision of one way that a house can be made.

Amrita has had to combine and synthesise prior knowledge and shape it to create and demonstrate understanding. Bill has likely had his knowledge expanded with greater complexity than Amrita and may have had opportunities for understanding opened to him. Evidence of understanding is more evident in Amrita’s house but it may also be occurring in Bill’s.

So which is the better way to learn?

I think it depends. If both Amrita and Bill have an existing provisional understanding of what a house is, then it’s likely that Amrita emerges with a more complex understanding. She now knows a lot more than Bill about how bits and pieces fit together and importantly how they don’t. Bill completely missed the opportunity to know what doesn’t work, and this can be a critical piece in our quest for understanding. Bill might know a bit more about one way to envision a complex house, but Amrita has a much more autonomous understanding of how to engage in the process of creating a house; she has certainly demonstrated an understanding of the concept “house” that Bill has not. He may or may not have a comparable understanding but this task doesn’t demonstrate his understanding and likely hasn’t allowed him to expand his understanding even if it has expanded knowledge.

But what if neither of Amrita or Bill had any knowledge of the concept they were building at all?

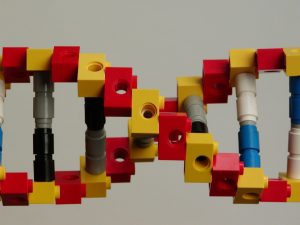

What if, for example, the task was to build a DNA molecule and neither Amrita nor Bill had any knowledge at all of molecular biology?

In this scenario, Amrita would really struggle. Without any vision of the final concept she is trying to construct, her lego pile would likely have to stay a pile.

Bill, following instructions from Denmark, could get straight into the construction process and quickly build an impressive DNA structure.

In this scenario, Bill has been much more successful in the building process, but what has he understood? Without some contextual learning about what a DNA molecule is and is for, his understanding about DNA may not be much more complex than Amrita’s pile of blocks. Bill may have come a little further than Amrita, but we would be mistaken to assume that because he has built a DNA molecule and Amrita hasn’t, that he has a significantly better understanding.

Building Understanding about Essay Writing

The lego metaphor has been prompted by some thinking around how we teach students to write essays. In Middle School, the essay, like the DNA molecule, is very new to students. As the lego analogy demonstrates, acquiring understanding when a concept is new is a challenge. Without some knowledge of the concept, understanding is limited; without some understanding, knowledge is limited.

What might applying the lego analogy to the teaching of essay writing look like?

In Amrita’s case, the method would be to say to Amrita something along the lines of “here’s a book with a bunch of ideas we’ve talked through in class, now I’d like you to turn your ideas into an essay.” Amrita, with little or no idea of what an essay is, would struggle to complete the task. Based on my experience of students new to essay writing, she would likely either write what she liked about the book or she would write a long collection of information about what is in the book. In both cases, her writing would lack any clear understanding of the purpose and form of an essay.

In Bill’s case, he would be given a very detailed rubric. The rubric would tell him exactly what to write in each paragraph, where to include quotes and how to start and end his essay. He would end with some knowledge of what an essay can look like but, as the lego analogy demonstrates, he may not end with much understanding.

The trouble with a detailed rubric is that it can give students and teachers a false sense of achievement but may not support transferable understanding. The trouble with no rubric is that students may not even begin to learn.

The challenge is to find the right balance between instruction and experimentation, the proximal zone for learning that best produces the desired outcome of understanding and mastery.

The art of teaching is often about finding this sweet spot between knowledge and understanding where learning will happen. This spot is different for every student on every task on any given day. Curriculum materials can’t provide this kind of specificity but they can provide this kind of flexibility.

Finding the Sweet Spot

What we’re learning at our school (UWCSEA) as we work in the Middle School with the Reading and Writing Project Units of Study, is that the best learning happens when we use a toolkit containing both instructions and freedom to experiment and explore. Neither Amrita’s freedom to experiment nor Bill’s tightly controlled instructions alone are going to efficiently produce understanding: true understanding happens when you have a much richer combination of both. It’s hard to get this right, but when you have checklists with just the right level of abstraction and models that are meaningful for students you have a good beginning. The other ingredient is a pedagogical framework that gives some instruction mixed with a good amount of time for students to experiment, get feedback, and try again.

What in the end I think I understand about understanding is that it is an emergent phenomenon; it can’t be taught but it can be learned. Crafting the right kind of learning environment is at the heart of this understanding.

Note: This article was originally published in 2016 in Ian’s personal blog ‘alternative carparks‘. Please visit his blog for more articles, poems, musings and great insights into many things in life.

Ian Tymms, BA (Hons), Dip Ed, M.Ed teaches Middle School English and High School Theory of Knowledge at The United World College of South East Asia in Singapore. He has been involved in the UWCSEA Curriculum Articulation Project and in the adoption of the “Workshop” approach to teaching literacy in the Middle School at East.

Ian grew up in Australia and studied English literature and Psychology at Melbourne University, with postgraduate studies at The University of Tasmania and Deakin University. Ian’s Masters research focussed on school cultures.

At the end of Grade 12, Ian was offered a scholarship to complete a 32 day Outward Bound course and he went on to work for Outward Bound Australia as an instructor. From this experience, Ian has retained a lifelong interest in Outdoor Education and Hahnian ideals. Ian has a passion for the outdoors and spends many of his holidays hiking in Austria or sailing in Australia with his wife, Sharon, and their two children.

1 comment