The debate between knowing facts vs knowing how to get to the facts is a hallmark of the discussion about the ‘education for future’, with the pendulum of opinion often swinging between the two opposite positions. In this article Nicholas Alchin brilliantly articulates some of the issues involved in this debate.

Students often ask why do we need to know this when we can just google it? It’s a great question, and it might indeed seem that with the internet as the fount of all knowledge, with facts only ever a click away, that there is less need to commit them to memory. It also seems to fit with the correct claim that creativity, critical thinking, communication, collaboration and other skills (some of which do not begin with ‘c’) are what we should be seeking to develop in our children, and we should therefore leave knowledge acquisition to focus on them instead.

However, the conclusion that knowledge is no longer important is profoundly mistaken for several reasons. I don’t want to focus here on the fact that relying on the internet for facts seems to have pushed us down a rather dark extremist path in recent years – but rather on something more fundamental to our cognition. The point is the rather counterintuitive one that it is precisely because skills like creativity and critical thinking are so important that we need to concentrate on knowledge. Let me explain, using examples from psychologist Daniel Willingham.

Take this sentence: Anna believed David when he said he had a house beside a small lake, until he said it was only 40 feet from the water at high tide. Anna was able to spot a problem in David’s claim because she knew something about lakes – namely that they do not have tides. If she had not known this, she would not have ever thought to look it up; or had she looked up ‘lakes’ she would have still been reading about geographical features long after David left the room. The point is clear – you need to know things; but it’s not obvious which things. And these are things that we cannot possibly specify in advance. How would Anna have known to brush up on tides and lakes before listening to David talk about his new home? Or consider: “I’m not trying out my new barbecue when the boss comes to dinner!” Mark yelled. We can automatically imagine the situation and likely understand the sentence. In doing so, we are drawing on knowledge about employment, status, barbeques, cooking with new equipment, social etiquette, and embarrassment and so perhaps can empathise with Mark. And again, we have to have all this in our heads so we can piece it all together – if you didn’t, we wouldn’t even know what we were missing, and what to look up.

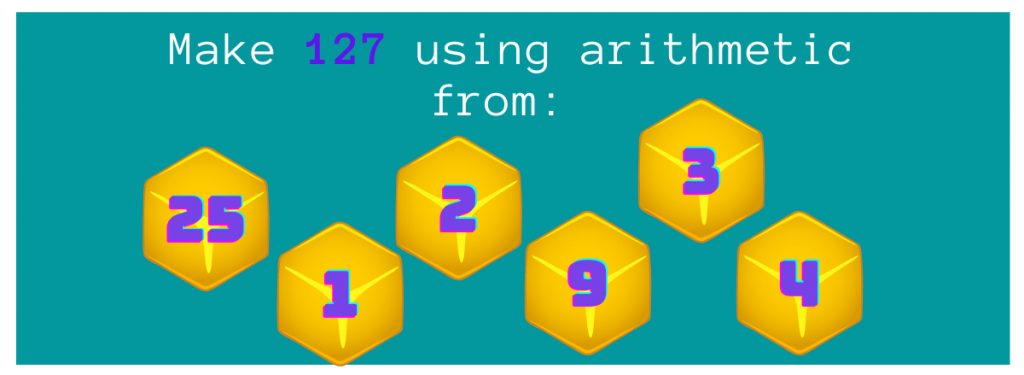

The issue goes further than just understanding; it also affects problem-solving capacity. Consider the countdown-type problem shown in the diagram.

Now, most people quickly see that (25 x 4) + (9 x 3) = 127 but only because most adults know automatically, without needing to calculate it, that 25 x 4 = 100, and 9 x 3 = 27, without any conscious effort or need for a calculator. If you didn’t just know these facts, at some deep level, then you wouldn’t know to work them out. You’d have to resort to the absurd mention of trying out various combinations (eg (9 + 4) x 25/(2 + 3) – of which there are several hundred thousand. Interestingly, the more facts you know, the more different and creative solutions you might find. Someone who knew, who just ‘saw’ that 125 = 25 x 5 might come up with 25 x (4 + 1) + 2 = 127; a mathematician who knew that 27 = 128 or 5! = 120 might well get to 2(3+4) – 1 = 127 or (4+1)! + 9 – 2 = 127. These are what we could typically call ‘creative’ but are completely based on firm knowledge that’s deep in memory.

So creative or critical thinking doesn’t somehow happen separately to what we know; facts are the bricks from which we build creative and critical structures. That’s why there is a fundamental and massive difference between things on google and things in our brains. If it’s not in long-term memory, it’s useless for critical or creative thinking. Looking it up just doesn’t cut it.

So if knowledge rich people have the capacity to understand more, to exercise greater critical analysis, to solve problems more readily, and even to be more creative, what does this mean as we seek to develop these skills? What does knowledge rich schooling look like? Well, contrary to many stereotypes, we do not need to adopt drill-and-kill and rote learning pedagogies. That won’t work because it’s simply not how people naturally learn. Take the information needed to understand the barbeque example from above – it’s not reducible to a list of facts, but it might be gained through social interaction with others, reading books about everyday life, discussions, dinner-table conversation, experiences of cooking, and so on – in other words, engaging in a rich life of varied experiences. The same transfers to the numbers example; beyond the basic timetables (which should be memorised) fluency and familiarity cannot possibly come by learning randomly 27 = 128 or 19 x 14 = 266 because there are simply too such facts to learn, because the facts would then be unconnected, and because most student would die of boredom. So to develop that knowledge we need to expose students to a rich range of situations involving number patterns and number relationships – puzzles, investigations, problems and so on.

All this speaks to varied, open work at school that exposes students to a lot of facts in meaningful contexts. If they collaborate and communicate on the basis of these facts then it will lead to deep knowledge that will support creative and critical thinking. So the knowledge emerges not as the end-product, but as a by-product of engaging in thoughtful, conceptually based tasks. It’s not so different to what we all want in most spheres of life – to retain the best of tradition, and to combine it with the best of new, progressive thinking too.

Note: This article was originally published in January 2021 in Nick’s personal blog ‘Education, Schools and Culture’. Please visit his blog for more such profound thoughts and deep insights into many things related to Education.

Nick has taught in holistic, values-driven schools schools since 1995, first teaching Theory of Knowledge and Mathematics at UWCSEA Dover and subsequently at the International School of Geneva in Switzerland. After working as Director of IB at Sevenoaks School, UK, and as Dean of Studies at the Aga Khan Academy in Mombasa, Kenya, Nick returned to Singapore to lead a team establishing the UWCSEA East High School in 2012 as the High School Principal. He was appointed Deputy Head of East Campus in 2016 and took up the position of Head of East Campus in January 2021.

IB Chief Assessor for Theory of Knowledge from 2005 to 2010 and Vice Chair of the IB Examining Board from 2007 to 2013, he is a textbook author, IB examiner, workshop leader and consultant who writes and speaks widely on various educational matters.

Nick has a bachelor’s degree in Natural Sciences from Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, postgraduate certificates in Engineering and Education from Wolfson College, Cambridge and Manchester College, Oxford and a Master’s in Educational Leadership from the Open University.

An avid reader, Nick also enjoys running in the heat, evening walks in the cool and baking bread each weekend. His three children enjoy activities from volleyball to podcasting to drumming, and Ellie, his wife, is Director of Teaching and Learning on Dover Campus. As a family they enjoy travelling across the region (when they can!), sampling new food, and enjoying the great outdoors.

3 comments