On behalf of Silver Pi, Susheela Menon talks to Lakshmi Karunakaran, who heads the Buguri Communities Library Program in Bengaluru.

Social impact organization Hasirudala’s children’s initiative — Buguri Community Libraries — impacts more than 1000 children of waste pickers and informal waste workers across Karnataka through its community libraries and education programs. With a collection of more than 3000 books, Buguri’s community libraries cater to over 500 children.

The initiative ensures financial support, hostel accommodation, mobile libraries, workshops that focus on sensitive issues like addictions or child marriage, and literacy programs that also build social cohesion.

Buguri faces fresh challenges because of the pandemic, but it also looks forward to building more child-led spaces for little children to explore, learn, question and grow.

On behalf of Silver Pi, Susheela Menon talks to Lakshmi Karunakaran, who heads the Program in Bengaluru.

Q: What does Buguri mean to the children that engage with it?

Lakshmi: Buguri means a spinning top.

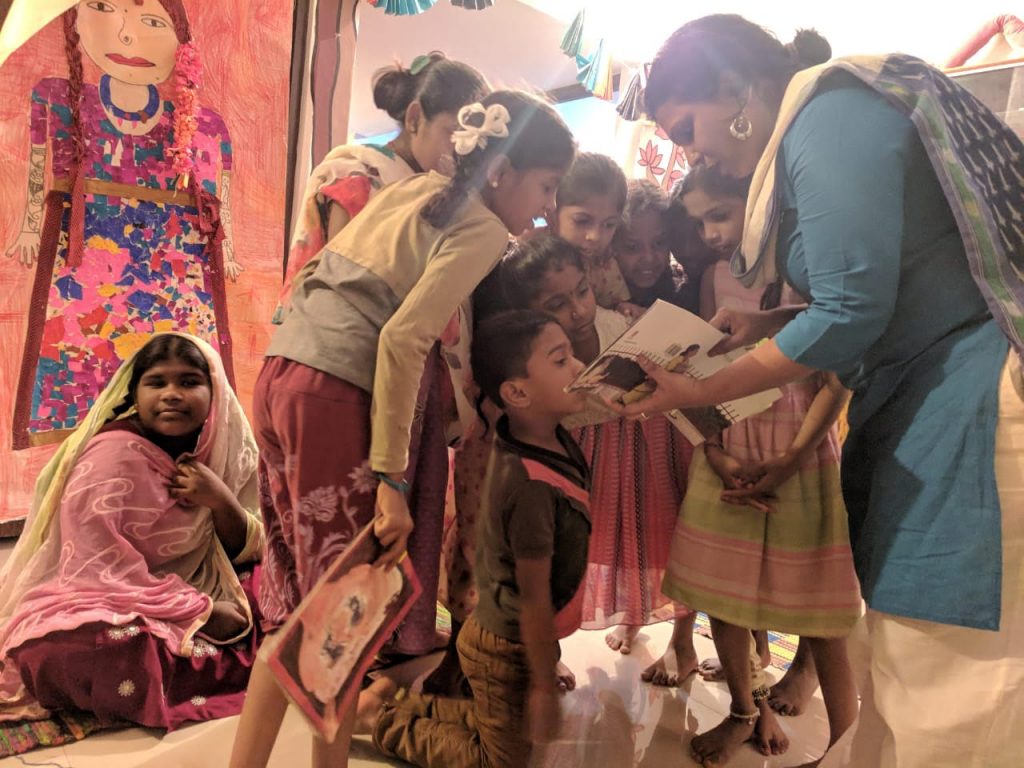

The idea was to create something that brings a turn in the lives of children, especially the children of waste workers who suffer extreme neglect. The libraries under the Buguri project are meant to provide safe spaces for the children to share their stories, process their thoughts, know a lot more about the world, and engage in activities that steer their journey towards a more positive direction.

Q: What were your goals when you started off with Buguri? Where do you stand now?

Lakshmi: We started in 2017 in Banashankari in Benguluru. Our aim was to engage the children of waste workers in a sustained fashion.

Today, we work in different places with both mobile and community libraries in six locations in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Every library is a small room filled with books but we know the impact it has on children. The little ones come in after school for different programs — read-aloud workshops, reading rooms, assisted reading — and we also operate a circulatory book model as well as a game room day where we have indoor and outdoor games. There are art room days where children are exposed to different kinds of arts and workshops that run for 3 to 4 months.

Our uniqueness lies in our ability to respond with specific interventions depending on the needs of the children in the community. The power of our program lies in our attempt to create a space that helps children understand, process and articulate what they feel using a medium or method that helps the process.

For example, in Tumkur, when COVID struck, some of the children turned to waste-picking because they didn’t have school. We identified these children and ran a 3-mlnth workshop in theatre. It was an eye-opener. After a month, the children had a production. They put together a play where they spoke about their everyday experiences. Some of them are super talented and made for the stage.

We also have a similar project in Mysore with kids researching their own community, especially the unique community of hair pickers that is mostly misunderstood and poorly documented. We trained 7 kids to do a multimedia article with recordings and illustrations so as to understanding hair picking and what it means to the larger world and the concept of waste management. It helped them understand their own worlds and taught them to be open to other worlds as well.

All our libraries have their own path. They are all in different places, the youngest being in Rajahmundry. Our oldest library is in Mysore where the children are involved in running it. The older ones engage themselves in research and writing while welcoming new children from all communities into their fold. The library plays a central role in the lives of these children and brings together communities that have seen major rifts in the name of caste and religion.

Q: What inspired you to spearhead Buguri?

Lakshmi: The Hasirudala team works with waste workers and when I joined them, we worked mostly with adults. Slowly, we realised that working with adults meant working with their children. We work for dignity of labor and identity rights, with much emphasis on policies that need to change.

Whenever we spoke about the future, we recognised that the children of many waste workers turned to the same profession because they dropped out of school. They needed proper education and access to more choices. We earlier had programs that helped support them economically by way of scholarships or loans, but I felt there must be sustained engagement.

And as I have personally benefited from libararies — especially the small one in my street that was such a powerful part of my childhood — I gravitated towards discovering those that had tried the common library mode in our bastis. I looked at these models in Bhubaneswar, Delhi, etc. and understood how they could be developed by us for the children here.

Q: Tell us more about your style of approach with regard to teaching children.

Lakshmi: We have always held the approach of facilitation and teaching. We want to make learning more experiential through books and stories to facilitate a certain learning process, not to have the talk-down approach.

We look at child-led processes. We look at children taking ownership of learning. The kids respond to that and to having an open space where every child walks in with the intention of being there. The space is meaningful to them. It sparks their creativity. It helps them think independently. It lets them question. It’s a unique space, a child-led space…and that’s what we want to nurture.

Q: How have your short-term literacy programs helped children that can’t read?

Lakshmi: When we began the project, we realised that some of the children couldn’t read. So we used the read-aloud technique and it worked like magic. We kept reading to them until they started to read. We intervene with storytelling, short term literacy programs, and research projects that focus on emotional literacy using picture books.

Q: What role does Buguri play in the intellectual and social development of children that come to it?

Lakshmi: We come from a community outside theirs so we are careful about where we stand. We can’t be those that disrupt their lives without understanding the consequences. When we bring up issues that are necesary — and we do — some of the disruptions are essential but we still don’t know the ripple effects.

There are issues of caste and class. We wait for the children to bring them up. We address their questions, their need to understand. This proved worthwhile because learning was triggered by the children at a time when they felt it was safe to discuss issues.

They then slowly questioned things that seemed normal to them earlier. That is the change we want. They want to talk about their communities, look at themselves with a different lens. They are growing in leaps in their own understanding. That has been very interesting to see.

We are now building a curriculum for them to understand caste and caste-based violence, so they process it in this space.

Q: What are the main challenges associated with running Buguri?

Lakshmi: This small ambition of using books and stories to open new worlds has received a big response and that has been so heartwarming. The libraries have become central to the lives of so many children.

COVID-19 has now led to many systems collapsing around us. Nothing we do is enough, but we are at it. Last year, we ran online and offline programs and also kept our doors open. There was a huge demand from the community. That was the only learning space the children got.

Besides, parents understood more about what we did, about how we engaged with their children. When the lockdown happened, we held online sessions and our librarians went door to door with books. Parents supported us tremendously and that strengthened our relationship so much.

Many challenges remain, especially now that India is seeing the second wave. Our healthcare system is collapsing. The largest learning opportunity of these children is being shut down with no alternative given.

We have otherwise dealt with multiple issues such as resources, space and funding, and people from all communities supported us. The international community helped. Other libraries helped. There was a sense of holding each other during tough times.

It’s becoming scary now. There is a peak in Bengaluru and we are minimising library interventions. We take a break when we have cases. Our most pressing challenge right now is to understand how to keep our programs running and relevant.

We are unsure about giving digital resources to little children as that’s not the kind of learning we want to propagate. We believe in contact and human connection. Technological interventions may limit our ability to handle the emotional aspects of working with children.

Q: Where do you see Buguri five years from now?

Lakshmi: Each of the libraries will be on different paths 5 years from now.

There will be 15 library projects in different phases and they will mature to a stage where the communities and kids will participate in their running. They will be community-led libraries.

I see older libraries going in that direction. We hope those that benefit from it will pay it forward. We have two staff members who come from the community the libraries are meant for, and we see the difference it makes when they directly communicate and work with the children.

It helps the younger ones see how the older ones did different things and gave a different direction to their lives. The children not only benefit from the space but also benefit from their ability to pay it forward. It will be very satisfying to see this happen.

Buguri’s official website: https://hasirudala.in/initiatives/buguri/

Susheela lives and works in Singapore. She has taught Creative Writing to primary school children for several years, and attempted online teaching amidst Covid chaos.

1 comment